In 2019, the Nuffield Trust published a review of NHS reorganisations[1] which set out major failures of past reforms, looking at the six major national plans since 2000. There were glimmers of hope that NHS England had read this when PCNs were first announced, because in our view they were intended to be locally-led, and because they did not require repetitive bidding for central pots of money. Despite this, the release of NHS England’s Draft Outline Service Specifications[2] for 2020/21 have been met with disgust by the majority of the profession. In this position statement, we outline what we feel are the reasons for this, and why without radical reform PCNs are in our view doomed to fail within two years of their release.

Funding

As always, the biggest problem is the money involved. Not, in this case, the total amount, but rather the method of delivery: accessing the available funding will result in practices losing hundreds of millions of pounds of their own money. The draft specifications repeatedly spin and obfuscate this fact:

“The GP contract framework, launched in January 2019, commits £978m of additional funding through the core practice contract and £1.799bn through a new Network Contract Direct Enhanced Service (DES) by 2023/24, as part of our wider commitment that, on current plans, funding for primary medical and community services will increase faster than the rest of the rising NHS budget over the next five years. By 2023/24 spending on these services will rise by over £4.5 billion in real terms – £7.1 billion in additional cash investment each year by the end of the period.”

Section 1.1

These are fantasy figures. Leaving aside the time-bending attempt to link funding five years from now to the January 2019 launch date, when precisely zero funding was available, the core practice funding mentioned is uplifts to the GMS contract which are nothing to do with the PCN DES. The losses incurred by an ‘average’ network, assuming it uses its full staffing entitlement each year at 70% reimbursement, and nationally assuming full utilisation of the staffing funding, are set out in the table below:

| Losses | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 |

| 50k PCN | -£17,400 | -£74,200 | -£152,900 | -£245,200 |

| National | -£110,100,000 | -£177,900,000 | -£271,700,000 | -£381,900,000 |

This further assumes that no further staff need employed to carry out the work set out in the specifications, that extended hours can be delivered for the reduce funding of £1.45/head available under the PCN contract, that PCNs incur no other costs whatsoever, and that the practices involved all give their time to make the networks run for free except for the single funded Clinical Director role. None of these are realistic: in reality this contract is a far larger cut to frontline NHS primary care.

Section 1.1 continues by cooking up ever-larger figures for the funding associated with the PCN DES contract:

“By 2023/24 spending on these services will rise by over £4.5 billion in real terms – £7.1 billion in additional cash investment each year by the end of the period.”

Where are these surprising, and ever-increasing amounts of money coming from? The source of the extra money is buried in the document:

“Funding previously invested by CCGs in local service provision which is delivered through national specifications in 2020/21 should be reinvested within primary medical care and community services in order to deliver the £4.5bn additional funding guarantee for these services.”

Section 1.24

The £4.5bn is not new money, but is at least in part taken from funding currently delivered to CCGs for them to provide Locally Commissioned Services. These existing, locally-led services, which patients can access now, are being cut by NHSE to make funding for the untested, centrally-imposed new DES contract look larger than it is. NHS staff and patients deserve better than this deliberately dishonest manipulation of the funding streams involved, and despite the warm words about stabilizing general practice, the draft is cutting existing funding before it reaches the first specification.

In practice, as Bucks, Berks & Oxon LMC have so ably demonstrated, the real cost of delivering the work associated with the PCN DES is likely to exceed these amounts because that work requires the use of GP time which is completely unfunded. The draft specifications look more and more like an exercise is political manipulation: a dizzyingly-large amount of money is theoretically made available through additional staff roles, but this is done in such a way that very little of it is actually spent.

More speed, less haste

The timing of the release of the draft specifications (on 23rd December) has come in for criticism given the proximity to Christmas, as has the short subsequent window for comments (by 15th January). While our view is that they should have been released whenever they were ready, the timing and its subsequent justification are cause for concern. These continue a pattern where NHS consultations, funding, and reforms are rushed, released at the last-minute, and inadequately thought-through or consulted on. No one can seriously suggest that a meaningful consultation on a year’s work can happen with those who will be doing that work can happen within three weeks, and when NHSE argue that the short timeframes are so they can put things in place by April, they are putting the cart a long way before the horse.

Furthermore, the specifications describe a series of noble goals which NHSE and CCGs have been trying to achieve for at least the past decade, through two previous NHS reforms, both of which have been rushed and have completely failed both patients and NHS staff. For these goals to now be hurriedly thrown at small organisations which have been in existence under a year is laughable, and making them contractual requirements by July, after a decade of national failure to achieve them, adds insult to injury.

Our proposed solution is to do one of them at a time. It’s a five-year plan, and there are five specifications. There should be detailed, measured consultation on which specification PCNs feel is achievable in the current year (our feeling is that SMRs should be first), with the addition of further specs in future years. The relatively trivial £75m in the Impact and Investment fund could then be bid for by those PCNs who wish to move forward with other specs in advance of their becoming requirements, and who have the strength to endure the bidding process.

As well as giving PCNs achievable targets for the coming year, this would allow NHSE meaningfully to assess the impact of a small number of things, rather than trying to assess the 80-odd requirements and metrics listed in the draft.

Care Homes

The care home element of the specifications is an incoherent, evidence-light, idiotic pandering to companies running care homes, at the expense of those patients who should have PCNs’ focus. Only a small proportion of these are residents in care homes: if you are an 85 year old with multiple diseases and complex care needs, the draft specifications mean you would get markedly worse care if you stay in your own home (where you’re ineligible for any of this spec) rather than going into a care home, where the same level of care is already more expensive. This is fundamentally inequitable.

If you scratch the surface of the noble-sounding rhetoric and look at the metrics, too, it’s clear that this section is driven by a desire not to improve care, but to reduce costs. The first two metrics are both related to reducing hospital admissions and attendance at urgent care centres, and the others are all metrics beloved of managers, not patients. Ask an elderly relative where in their personal priority list they would rank “receiving a delirium risk assessment”, or “having a personalised care and support plan” – these things are meaningless as metrics because they are not outcomes, and are therefore also irrelevant to patients care.

Particularly objectionable is the requirement for weekly reviews of all care home patients. Words cannot adequately express how fantastical it is to suggest that this is achievable, but BBOLMCs have outlined some of the figures demonstrating this.

The Office of National Statistics said in 2017 that there were 410,000 patients in care homes. Although this will have risen since in line with the rising elderly population, we will work from these numbers to be kind to the specs. We know we are expected to spend “longer than an average GP appointment” on these reviews – so let’s assume they’re 20 minutes.

This is an extra 7.1m hours of time annually, rising in line with the aging population, with 3.55m of those hours mandated to be delivered by GPs (although it’s theoretically possible for a community geriatrician to do this work, it will be difficult to persuade any of them to come work for PCNs for free). There is, of course, a GP workforce crisis, meaning that there’s no one to do this work, but let’s assume there were; if you allow £80/hour for a GP’s time, and take the number of practices 7,000, this will cost about £284m nationally, with every practice paying about £40,000 a year to deliver. This work is completely unfunded.

This section also raises the spectre of these numbers being boosted by those in “supported living environments and extra care facilities” in future, as well as the responsibility for OOH care (which, like GP workforce recruitment and retention, is a national disaster area) being lobbed in the direction of PCNs in future.

What this requirement amounts to is a huge, completely unfunded, underwriting of the profits of private companies delivering care home services. Disappointingly, there is no evidence that thought was given to what this work would require, how it would be paid for, or what the impact on the existing workforce would be of our supposed “huge funding boost” taking this ludicrous form. We propose doing away with this specification in its entirety.

Measure what matters

The old adage that organisations tend to measure what’s easy to measure rather than what matters very much applies here, and we’ve touched on it above regarding the care home metrics. Overall, the draft specifications are laden with metrics. These are contradictory in places, confusing, frequently irrelevant, and will – based on the long experience of primary care in delivering DES work – be onerous and irritating to report on.

Depending on how you count the specifications, some of which are numbered, some bulleted, and some surreptitiously sub-bulleted, there are 50 specifications and 33 metrics in the draft specs. That’s 83 things for every PCN to look at. PCNs are small, newly-formed and untested organisations, and drowning them in paperwork is not the way to get them to achieve results for their patients. More to the point, NHS England have tried this approach, of endless detailed “measurement”, in every historical reform it’s been responsible for, and it has never worked. At the risk of drowning this section in aphorisms, those who fail to learn the lessons of history are doomed to repeat them.

Some of what is put out for measurement smacks of bandwagon-jumping, too. It is impossible to take its commitment to tackling climate change seriously, for example, when in one breath the document champions the use of low-carbon inhalers, and in the next it requires written, paper invitations sent to hundreds of thousands of patients nationally.

We would propose dispensing with all the metrics. Patients don’t care about the vast majority of them. Let PCNs do what they feel is important, and justify that to the centre perhaps twice in the year, at six and twelve months. Some will undoubtedly try things that don’t work. This should be regarded as a positive learning experience, rather than a failure of process.

Understand what “accountability” is

On a related note, NHS England must drop the anxious thread that runs through all their policy documents which sees them desperate to mention “accountability” at every turn. Of course they have a duty to see that public money is spent responsibly. However, primary care is the most efficient, cost-effective, and worst-funded part of the health service. We have always spent public money responsibly, a huge part of our work is helping patients understand that NHS provision is not endless, and – bluntly – we are much better at this than NHSE are.

When we read the repeated calls for clinical leads for each ‘priority’ – again, all completely unfunded – and for these people to be “accountable for service delivery”, we do not see this as the righteous call of an organisation demonstrating its fiscal responsibility. We see it as NHSE seeking someone else to blame if its reforms fail: it will be the fault of the many clinical leads, who were accountable, not of the organisation behind the reforms.

It is worth NHSE reflecting on the message this sends to frontline staff, none of whom are in any doubt as to their accountability for the care they provide.

Let local areas lead

The current draft specifications lean heavily on one-size-fits-all, centrally-imposed metrics of “success”, where success is defined by NHSE and not by the local PCNs. An entire section, “Supporting Early Cancer Diagnosis”, falls into the precise trap outlined by the Nuffield Trust of focusing on a single disease, and the majority of the metrics do likewise.

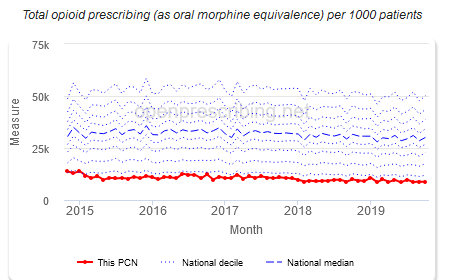

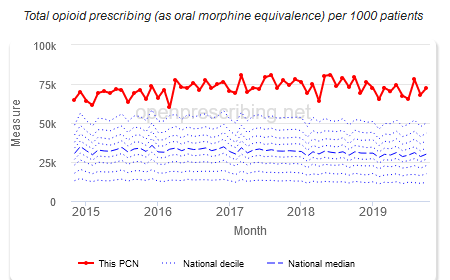

Several excellent tools, like OpenPrescribing[3], are referenced in the draft specifications, and a glance at these with reference to PCNs demonstrates the absurdity of imposing central targets on PCNs. Compare the rates of opioid prescribing between the two PCNs shown below:

The first PCN is wasting its time, national resources, and its patients’ time by trying to reduce opioid prescribing rates which are already in the lowest decile nationally. By contrast, the second PCN can probably benefit from doing so. This sort of discrepancy, also, does not reflect better or worse provision of primary care: it reflects demographic differences between areas which the imposition of central targets completely overlooks.

PCNs should have the freedom to look at whatever areas they feel would most benefit their patients, using the existing resources out there. These resources, like OpenPrescribing or the Public Health England Fingertips site, are useful and thought-provoking precisely because they take the time to look at local data.

The profession will not accept ‘drift’

The psychological concept of starting with a high ‘reference price’, so that the person you’re negotiating with regards anything better as a bargain, has been mentioned in relation to the draft specifications. The argument is that NHS negotiations typically start with something utterly appalling, so that when something slightly less dreadful is imposed on PCNs in a few months’ time, they regard it as less bad than had that been the opening offer.

The response to the draft specifications has been so universally condemnatory that one hopes this won’t work, particularly given the historical tendency for DES requirements to be subsumed, in later negotiations, into the core contract. This would be disastrous for the profession.

Conclusion

While there are some well-meaning ideas in the draft specifications, the document is an incoherent, buzzword-heavy, dishonest, politically-motivated mess. NHS primary care, and the patients it serves, deserve better than a document groaning under the weight of its own spin. We would urge GPs and community organisations around the country to respond to the consultation, and resoundingly to reject any final set of specifications which even slightly resemble the draft release.

[1] Avoiding groundhog day: learning the lessons of NHS reforms. Nuffield Trust, 16/10/2018.

[2] Network Contract Direct Enhanced Service: Draft Outline Service Specifications. NHS England.

[3] OpenPrescribing.net, EBM DataLab, University of Oxford, 2020